Highbury Corner Magistrates Court are currently presiding over the charges against student Konstancja Duff over alleged claims she assaulted a police constable in July 2013. The initial incident to spark the arrest and subsequent alleged assault was an act of sporadic mark making as Duff chalked a protest slogan over a stone plaque at a UoL campus. In a discourse of common sense we understand Duffs actions as a basic exercise of speech – or further, a need to make her speech public. Through publishing her speech she exercised a well established and understood action within modern protest repertoires, employing the use of image production as a method for disseminating a shared belief.

Duff’s arrest is a clear indicator that institutions and governments still fear the potential social power of a successfully mimetic image. Images as language are dangerous as governing bodies lack an ability to control the spread of the ideologies they transmit. We live within a society in which image reproduction can re-produce any piece of visual self-politicisation into something revolutionary, and through contemporary developments in online self-organisation protest strategies, their reach is impossible to limit. To the governing arm silently controlling The Met, it’s too easy to make individuals like Duff become Gilliam’s Sam Lowry.

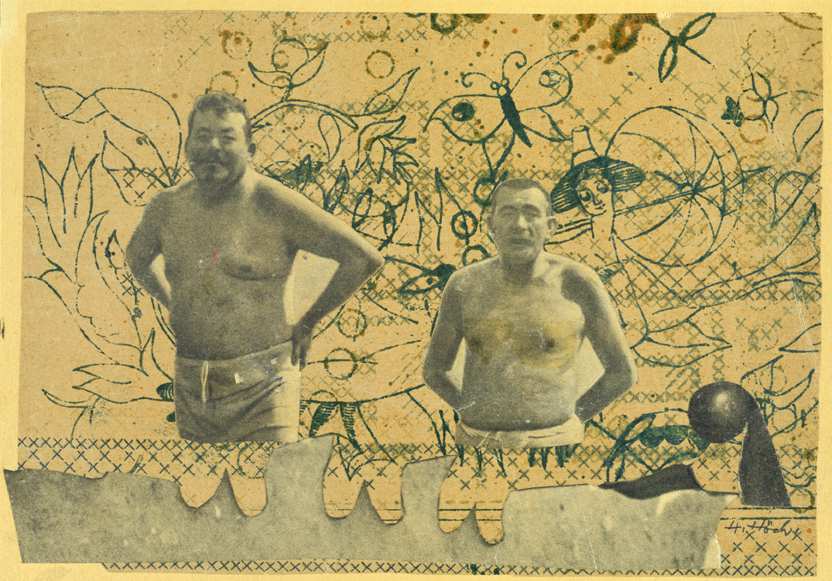

Hannah Höch, Staatshäupter (Heads of State), photomontage, 1929. Courtesy Collection of IFA, Stuttgart and Whitechapel Gallery London

Duff unfortunately isn’t alone, as numerous similar cases are becoming an increasingly regular part of our current social experience. With this in mind, the Whitechapel Gallery‘s Hannah Höch exhibition should be identified as the staging of an important public discourse on the possibilities of the graphic image as a discursive weapon in political activism. Höch’s involvement with the anti-establishment Dadaists provided the foundations of her collage based practice splicing images drawn from contemporary culture and repackaging them to deliver social and political satire.

The Dadaists were fundamentally art radicals forming a networked protest movement: anti-establishment and anti-bourgeoisie. Therefore the highlighting of these very explicit political narratives is something that should of course be key in orchestrating what is in some way a retrospective of Höch’s practice. However, unfortunately, the Whitechapel appear to have bypassed this. There is something troubling upon entering an exhibition of Höch’s work to encounter an arguably incredibly institutional archival curatorial model. Applying a strict rationality to the curatorial framework within which her work sits through a chronological linearity feels in some way to dangerously answer or explain the content, providing cliché ready made judgments suggesting a simpleness to the progression of the subversive nature of her core ideologies and conceptual concerns.

Höch’s Dada good girl reputation should have been smashed through this exhibition. We were offered tantalising glimpses into her androgyny and lesbianism, anti colonial social commentaries, satirical attacks on imperial power structures and revolutionary statements on gender politics. I’d really hoped for a curatorial model in which ideas could be grouped and concerns shared spanning across bodies of work.

Hannah Höch, Ohne Titel, aus der Serie: aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Untitled, from the series: From an Ethnographic Museum), photomontage with collage,1929. Courtesy Federal Republic of Germany – Collection of Contemporary Art, Kupferstichkabinett, SMB / Jörg P. Anders and Whitechapel Gallery London

Reconsidering Duff, imagine how powerful a conversation between Staatshäupter and Ohne Titel, aus der Serie: aus einem ethnographischen Museum could have been at opening a discursive space over presentations of imperial power within colonial European states and the space for female activism and how relevant they are for contemporary radicals like Duff. Metahaven identifies the joke, or use of humour, as a dangerous political weapon: drawing upon reference points such as Bepe Grillo; Rickrolling; LOLCats etc. Can Jokes Bring Down Governments suggests the activation of irony spread through a meme, or cultural gene, through a process of reproduction, can act as an unstoppable force of revolutionary politics. These phenomenon are so incredibly relevant to the practice of Höch. I’d hoped in some way that these strategies would be in some way have been allowed to become explicitly visible.

The exhibition however, is absolutely worth visiting regardless. The collection of her work across the gallery space, which hypocritically I will state, is spatially beautiful and elegant. It’s just disappointing that the desired elegance has applied such an overbearing formalism over such an enigmatic anti-formal figure.

Hannah Höch is running until the 23rd March.

Visiting information and hours can be found on the Whitechapel website.